The temporary use of vacant spaces is still a pretty new phenomenon in Helsinki, but it seems to be making its way fast on the public agenda.

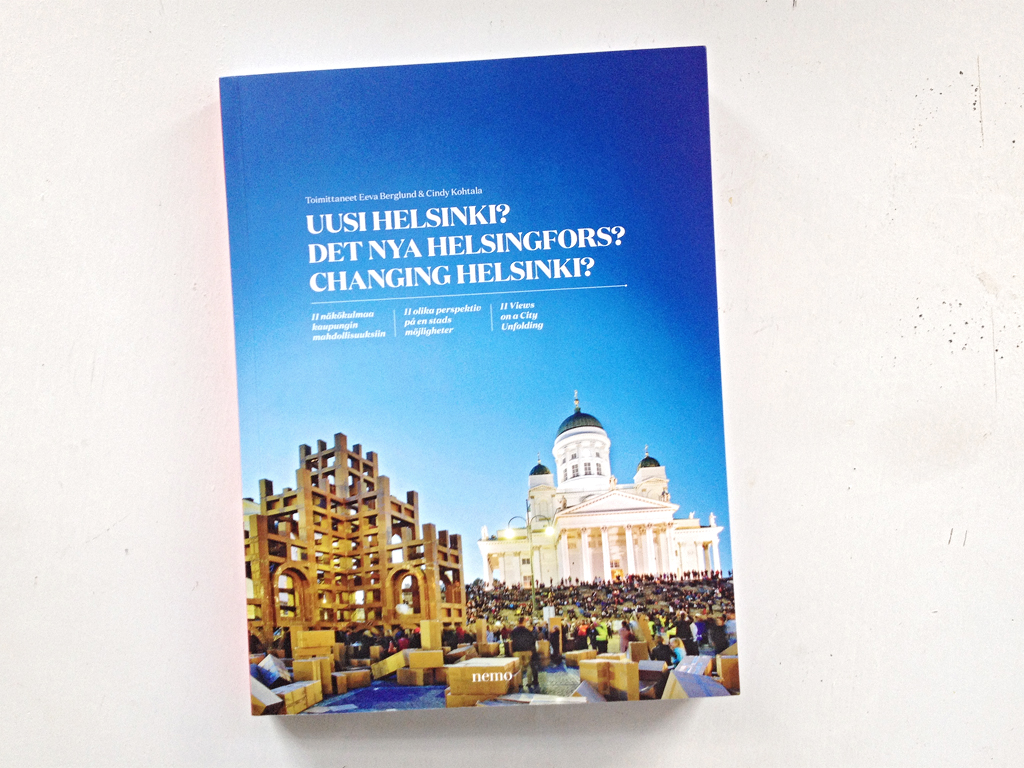

In the recent few years, major infrastructural changes, such as the relocation of Helsinki’s inner city harbors to the eastern suburb of Vuosaari, have made large areas available for new developments within the inner city, and many former industrial buildings are lying in wait for their future development. The potential for temporary use of these locations is unique, and at the same time the creative energy of Helsinki’s current grassroots activities is tangible. Areas under transformation serve as catalysts for new things and ideas. Open playgrounds, such as Kalasatama harbor in Helsinki, have become new stages for civic grassroots activities. The harbor warehouse “L3” in Jätkäsaari (which is home to Urban Dream Management headquarters) is being filled with startup businesses, art projects and creative networks. Very often a challenge still remains: how will the existing vacant spaces meet their users? And, what will happen after the temporary use of one location comes to an end?

Yesterday’s Sarana seminar, organised by Helsinki Economic Development, offered a broad overview into the potentials and challenges of temporary use from many different angles. Sarana is Finnish for hinge – the name of the seminar referred not only to opening the doors to vacant spaces but also to those two parts linked together that form the hinge. Temporary use is often a platform where different disciplines and activities, like culture and new business, are linked together. Often it is a question of how the potential users and real estate owners could find a way to meet each other’s demands.

The Sarana seminar was the outcome of the Luova pääkaupunkiseutu (Creative metropolitan region) project, which investigated temporary use both on the level of city administration and on the level of practice – and there lies its potential to really open the doors towards enabling more temporary use in reality.

The seminar was a rare occasion where many different parties – city administration, grassroots actors, designers, researchers and real estate owners – sat around the same table and presented their different practical perspectives to the topic. This kind of discussion is really needed to enable temporary use in practice – as it is often precisely the lack of dialogue and understanding between these different parties that forms the biggest obstacles in reality.

As the benefits of temporary uses are already acknowledged – they often create multidisciplinary platforms for culture, creative businesses and start-ups and thus also have a significant impact on the image of a location or a city, not to mention that they offer a chance for direct and concrete citizen participation and even bring short-term financial benefit for real-estate owners – it is clear that cities should endeavor to work on policies that better enable these positive outcomes. The main bottlenecks for temporary uses are often in the complex bureaucratic structure and regulations and in the lack of information. A proper official policy regarding temporary use in Helsinki doesn’t exist yet, but this project clearly is a step towards creating such a strategy in the future.

The panel brought into attention the significance of temporary use, especially its image effects, of which all seemed to agree. Yet, it is important to understand the user perspective as well. Temporary users are often grassroots players who are developing new culture, new businesses or new societal projects, often at least partly as voluntary work. As the positive impacts of their projects, not only economical but even more importantly, socio-cultural and ecological, are acknowledged, how could these be better nurtured and supported? What happens when the temporary use of one location comes to an end but the activities would still continue to need spaces?

The seminar offered one clue to this, an idea that has come out also earlier in several research projects. If temporary uses are to be taken seriously and placed at the very nucleus of urban politics and planning, a sort of an “urban agent” would be needed: someone, perhaps a new city official, who understands both users and owners and helps people navigate in the jungle of bureaucracy. This agent could also coordinate the available spaces, offering the users new spaces when others are no longer available.

Helsinki is now bubbling with all kinds of innovative and active grassroots actions, where people work together towards making their city a better place. Our strong local culture of grassroots innovation is still an underutilized resource – but it has the potential to really make Helsinki the best place in the world. Now would be an opportunity to take a step further from one-off events and single short term activities towards harnessing this potential into more long term developments.

—

The Sarana seminar was also the launch of a magazine under the same name. This publication, unfortunately only in Finnish, is a great overview into the practice of temporary use in Helsinki at the moment. Urban Dream Management’s contribution, which discusses the warehouse L3 where our headquarters are located, can be found on page 33. Have a look here!

One Response

Hannaliisa Johnson

Thanks Hella for this blog!